2014-04-15

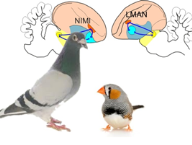

Whenever we perform a movement repeatedly, we never do it exactly the same way. There is always variability. This variability in the motor output is often viewed as noise in the system. In contrast, recent findings show that variability is more than that. Motor variability plays an important role for learning of new skills and is actively produced and regulated. Part of these findings stem from research on song birds like zebra finches. During song learning – a motor skill similar to human speech – a specialized forebrain area termed lateral magnocellular nucleus of the anterior nidopallium (LMAN) conveys variability into the motor output. Interestingly, pigeons as non-song birds possess a brain region that is possibly homologous to LMAN. This region is named nidopallium intermedium medialis pars laterale (NIML). Researchers of the Biopsychology lab together with theoretical neuroscientist from the University of Bremen have devised an experiment to test the role of NIML for behavioral variability. Pigeons learned to find hidden targets that were randomly placed at different locations on a touch screen. The researchers’ results show that their experiment induces highly variably pecking behavior. However, transient pharmacological inactivation of NIML did not result in reduction of variability. Hence, the researchers argue that in contrast to LMAN the pigeon’s NIML is not associated with behavioral variability. Together with previous findings this result suggests that LMAN’s role for variability generation in song bird is an adaptation to the special demands of song that evolved from old motor pathways of a common ancestor of recent birds. In contrast, this adaptation was not necessary in the motor system of pigeons or alternatively was lost during evolution.

Whenever we perform a movement repeatedly, we never do it exactly the same way. There is always variability. This variability in the motor output is often viewed as noise in the system. In contrast, recent findings show that variability is more than that. Motor variability plays an important role for learning of new skills and is actively produced and regulated. Part of these findings stem from research on song birds like zebra finches. During song learning – a motor skill similar to human speech – a specialized forebrain area termed lateral magnocellular nucleus of the anterior nidopallium (LMAN) conveys variability into the motor output. Interestingly, pigeons as non-song birds possess a brain region that is possibly homologous to LMAN. This region is named nidopallium intermedium medialis pars laterale (NIML). Researchers of the Biopsychology lab together with theoretical neuroscientist from the University of Bremen have devised an experiment to test the role of NIML for behavioral variability. Pigeons learned to find hidden targets that were randomly placed at different locations on a touch screen. The researchers’ results show that their experiment induces highly variably pecking behavior. However, transient pharmacological inactivation of NIML did not result in reduction of variability. Hence, the researchers argue that in contrast to LMAN the pigeon’s NIML is not associated with behavioral variability. Together with previous findings this result suggests that LMAN’s role for variability generation in song bird is an adaptation to the special demands of song that evolved from old motor pathways of a common ancestor of recent birds. In contrast, this adaptation was not necessary in the motor system of pigeons or alternatively was lost during evolution.